Seppala Siberian Sleddog

Why the Seppala Siberian Sled should be Maine’s State Dog

The Poland Spring Preservation Society is excited to announce with the help of David Boyer, our Maine Legislator, our commitment to support the nomination of the Seppala Siberian Sleddog as Maine State Dog. On December 5, 2024 our board unanimously voted to support this initiative.

There is strong connection between these superior dogs and Maine. Northeastern Siberia is a land of vast expanses and great contrasts, a land cut in half by the Arctic Circle. Dogs were held in high esteem by the people who lived in this land because their existence often depended upon their sled dogs. These sled dogs were the ancestors of the present-day Seppala Siberian Sleddog. Imported to Alaska early in the 19th century.

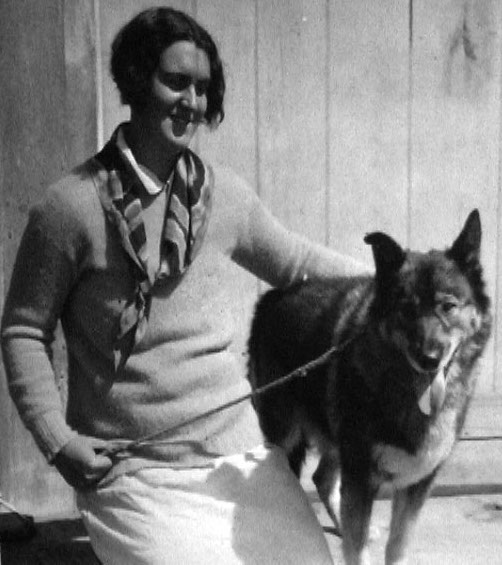

Leonard Seppala and Elizabeth Ricker on Range Pond

Maine’s Heritage Dog Breed

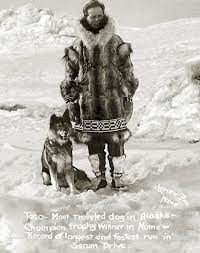

On January 27th, 1925, Leonhard Seppala and his dog sled team featuring the legendary dog Togo, transported serum across the frigid, dark, and perilous landscape of Alaska to save the children of Nome from a severe diphtheria outbreak.

Did you know that Maine has a deep connection to this heroic event? In fact, Maine boasts a mushing heritage that rivals any other state. Robert Peary, the first man to reach the North Pole, launched his expeditions from his home in Maine. Additionally, Lewiston native Mush Moore famously led a dog team from Fairbanks, Alaska, back to Lewiston, Maine. Today, the Can-Am Crown International Sled Dog Race in Fort Kent continues to celebrate Maine’s rich mushing tradition.

Following the rescue of Nome’s children, Leonhard Seppala collaborated with Elizabeth Ricker of the historic Poland Spring Resort to create the first Seppala Siberian Sleddog kennel right here in Maine. Together, they dominated the racing scene in the northeastern US and Canada with their Maine-bred Seppala Siberians for nearly a decade.

In fact, New Hampshire’s state dog, the Chinook, is a sled dog breed that consistently lost to Maine’s Seppala Siberians. The legendary Togo lived, bred, and died right here in the Pine Tree State. Just two years ago, a monument to Togo was erected at the Maine State Building in Poland Spring, Maine.

The Unveiling of Togo – by David Smus

To celebrate this centennial, there is a undertaking to honor our state’s rich mushing heritage and to have the Seppala Siberian Sleddog named the official state dog. There are currently 13 other states with official state dogs. Two other New England states already have sled dog breeds as the canine representatives of their state.

Below is more information about this amazing Seppala Siberian Sleddog and it’s heroic heritage.

For more information email:

David.Boyer@legislature.maine.gov

Cyndi@polandspringresort.com

Jonathannathanielhayes@gmail.com

Seppala’s Role in the “Great Race of Mercy” of 1925

A diphtheria outbreak struck Seppala’s town of Nome, Alaska, in the winter of 1925. Previously unexposed children, as well as adults, were at risk of dying from the infection. Seppala’s only child, an eight-year-old daughter named Sigrid, was also at risk. The only treatment available was diphtheria antitoxin serum. However, Nome’s supply of serum was not only insufficient but also of presumably low efficacy, being past its expiry date. Without the antitoxin, estimated mortality rates stood anywhere from 75% to 99.99%, practically a killing blow to Nome. The only practical way to deliver more serum to Nome in the middle of the coldest winter in 20 years was by dog sled. A relay of respected mushers was organized to expedite the delivery, and Seppala (with lead dog Togo) was chosen for the most forbidding part of the trail. The serum was to be taken by train to Nenana, Alaska, and from there relay teams would set out from Nome and Nenana, meeting in the middle at Nulato.

The whole trail was 674 miles from Nenana to Nome, and Seppala was initially selected to cover the more than 400 miles from Nome to Nulato and back. Seppala’s section of trail featured a dangerous shortcut across Norton Sound, which could save a full day of travel. It was decided that he was the most qualified of the relay mushers to attempt this shortcut. The ice on Norton Sound was in constant motion due to currents from the sea and the incessant wind. It ranged from rough hills of smashed-together ice to slippery “glare ice” polished by the wind, where it was difficult for the dogs to get a foothold. Small cracks in the ice could suddenly widen and driver and team could be plunged into the freezing water. If the wind blew from the east, it could reach speeds as high as 110 mph (180 km/h) flipping over sleds, pushing dogs off course, and causing a windchill as low as −116.5 °F. A sustained east wind could also push the ice out to sea and a team caught on a drifting floe could find itself stranded out on open water.

Seppala had taken the shortcut across the Sound several times in his career; a less-experienced musher was more likely to lose not only his life and the lives of his dogs, but also the urgently needed serum. Seppala would cross the sound each way in the race to deliver the serum.

Seppala set out from Nome on January 28, several days before he was due to meet the relay coming to Nulato. He crossed Norton Sound without incident. Meanwhile, the number of diphtheria cases in Nome continued to climb. To hasten delivery of the serum, more mushers were added to the relay from the south. However, it was too late to inform Seppala that he would be meeting the relay closer to Nome than had originally been planned. After 3 days and 170 miles, he came in sight of another relay musher, Henry Ivanoff. Seppala saw the musher stopped on the trail and having trouble with his dogs, but did not intend to stop and be delayed. Ivanhoe had to run after Seppala as he raced past, shouting, “The serum! The serum! I have it here!”. When the serum passed to Seppala, night was falling and a powerful low-pressure system was moving towards the trail from the Gulf of Alaska. Seppala had to decide whether to risk Norton Sound in high winds in the dark, where he could not see or hear potential warning signs from the ice. Since going around the ice meant slowing the delivery of the serum by a full day, he chose to go across Norton’s Sound. While he raced to the roadhouse at Isaac’s Point on the opposite shore, gale-force winds drove the windchill to an estimated −85 °F from a real temperature of only −30 °F. When he arrived there at 8 pm, his dogs were exhausted; they had run 84 miles that day, much of it against the wind and in brutal cold. However, they could only afford a short rest, and set out again at 2 AM.

The next day, the gale had intensified into a severe blizzard with blinding snow and winds of at least 65 mph. Seppala continued the trail across Norton Sound. This meant avoiding rocky cliffs along the shore, but it also exposed him and his team to the dangers of the Sound. Conditions on the ice were perilous, with sudden soft spots in the ice underfoot and outright open water sometimes only a few feet away. Only a few hours after they had crossed it, the ice broke up altogether and drifted out to sea. With Norton Sound behind them, Seppala and his team now faced the final challenge of the trail—climbing an 8-mile ridge formation that led to the summit of Little McKinley. The trail here was exposed and the steep grade grueling for the dogs who were sleep-deprived and had already raced 260 miles over the previous days. Despite this obstacle, at 3 P.M. that day, Seppala and his team arrived at Golovin and handed over the serum to the next musher. The serum was now only 78 miles from Nome. Thankfully, it arrived there the next day, Monday, February 2, at approximately 5:30 A.M., and was thawed and ready for use by 11 AM. This emergency delivery, also known as the “Great Race of Mercy”, is commemorated annually with the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race.

The Maine’s Connection

The story of Leonhard Seppala, his lead dog Togo, and his team of Siberians is the stuff of legends. Children’s books have been written and Disney has made several movies, both animated and live action, to cash in on their heroic tale. The abbreviated tale is this:

In January 1925, during the coldest and darkest days in the low Arctic, Leonhard Seppala and his team fought -50F temperatures, blinding blizzards, and crossed miles of broken sea ice—twice—to save the children of Nome, Alaska from a deadly outbreak of diphtheria. “The End”?

This is usually where the Disney stories end. But that is where Maine picks up the story. After a grand tour of the lower 48 states in the winter of 1926/1927, Leonhard Seppala, Togo, and the team were invited to Poland Spring Resort in Maine to race against famed explorer Arthur Walden’s team of Chinooks. Despite the team being out of condition due to the lecture circuit they had just ended, Seppala and his Siberians handily beat all the New England competitors, including New Hampshire’s state dog—the several teams of Chinooks in the race.

After the win, Elizabeth Ricker of Poland Spring made an offer that Seppala could not refuse: partner with her to establish the first Seppala Siberian Kennel, right here in Maine. For the next decade, Seppala and Ricker bred, trained and raced these dogs here in Maine and dominated the race circuit throughout New England and eastern Canada, including an exhibition race at the 1932 Olympics in Lake Placid, New York.

For the past 25 years, I have carried on the legacy as one of only a handful of kennels of this heritage breed at our Poland Spring Seppala Kennels, here in Maine. Our working dogs are registered purebred descendants of Togo and that original and heroic team of Seppala’s dogs. For the past 4 years, I have also served as the president of the International Seppala Siberian Sleddog Club. This January, on the centennial anniversary of their ancestors’ heroic deeds, we will be mushing a Maine bred team of Seppala Siberians on a twenty day expedition across the low arctic, retracing the trail their ancestors took to Nome, Alaska, one hundred years ago.

In 2011, Time Magazine named Togo, the wellspring of the Seppala Siberian breed, “the most heroic animal of all time.” Thirteen states have official state dogs. Our neighbor to the west, New Hampshire has honored their legacy by making the Chinook Sled Dog their official state dog. Alaska chose the “Alaskan Malamute” as their state dog. Simply put, no other breed of dog can lay claim to the distinction of “Official Maine State Dog” with as much history, honor, weight, and distinction as the Seppala Siberian Sled dog. I, therefore, wholeheartedly support the effort to make the Seppala the official Maine state dog and humbly urge you to do all you can to support the effort as well.

Jonathan Hayes, Musher Poland Spring Seppala Kennel

Centennial Seppala Expedition 2025

On January 27, 2025 at 10am (AK time) Jonathan Hayes and his team, will recreate history spending the next two weeks traveling from Nenana to Nome, a distance of 700 miles. This is to celebrate 100 years since the original Serum Run made famous by Leonhard Seppala and his dogs Togo, Fritz, Balto & Fox. Jonathan’s dogs taking part in this expedition are direct descendants of Seppalas dogs and will be traveling the exact same route traveled all those years ago by a relay race of brave mushers and their sled dogs. UPDATES HERE

Objectives:

1. Historical Commemoration: To retrace the historic serum run route and honor the legacy of Leonhard Seppala, Togo, and the other mushers and dogs who played a pivotal role in the 1925 serum run.

2. Public Awareness: To increase public awareness about the historic significance of the serum run, the challenges of early 20th-century expeditions, and the ongoing importance of sled dog teams in Arctic exploration.

3. Scientific and Cultural Documentation: To document the expedition through various media, including film, photography, and interviews, capturing both the historical significance and contemporary challenges of such an endeavor.

4. Educational Outreach: To create educational content and programs that will inspire future generations about the spirit of exploration, teamwork, and resilience.

Letter of Support from the Poland Spring Preservation Society

Poland Spring has been a notable destination since 1794, with historical developments including a world famous resort and the bottling of Poland Spring Water. The Poland Spring Preservation Society’s mission is to preserve the Maine State Building and All Souls Chapel, key elements of our states heritage. The Society is run by a volunteer board and staff, ensuring the protection and restoration of these unique structures. The Maine State Building was originally built in 1893 for the Chicago Worlds Fair also known as the Colombian Exposition. The Fair was to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus. All 44 states, dozens of countries, and even companies sent buildings to the grounds to participate in the grand event. In total, there were almost 200 buildings on the grounds. The Maine State Building, built entirely of Maine wood and stone, is one of only 5 buildings remaining. Several years back, after the Disney movie was released, the board decided to honor Togo, who had retired here, with a bronze statue.

Maine State Bill and co-signers

Description of a Seppala Siberian Sleddog from the Continental Kennel Club

Letter of Support from the current owner of Poland Spring Resort

Letter of Support from President of the Seppala House Project

Letter of Support from the Selectman from the town of Poland, Maine